- Video with Q&A.

- Simple workload (serving static pre-encoded media files) on a FreeBSD/Nginx stack.

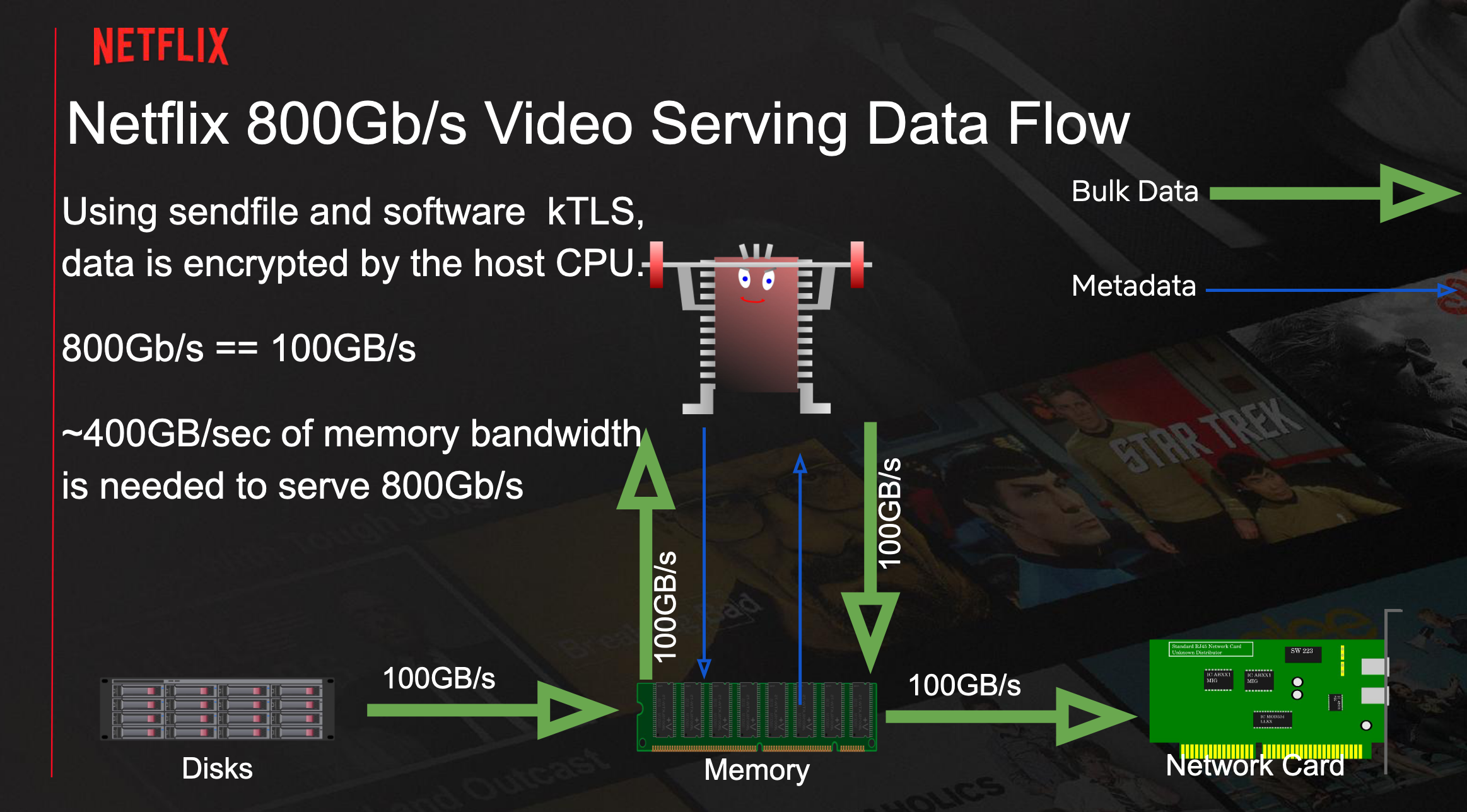

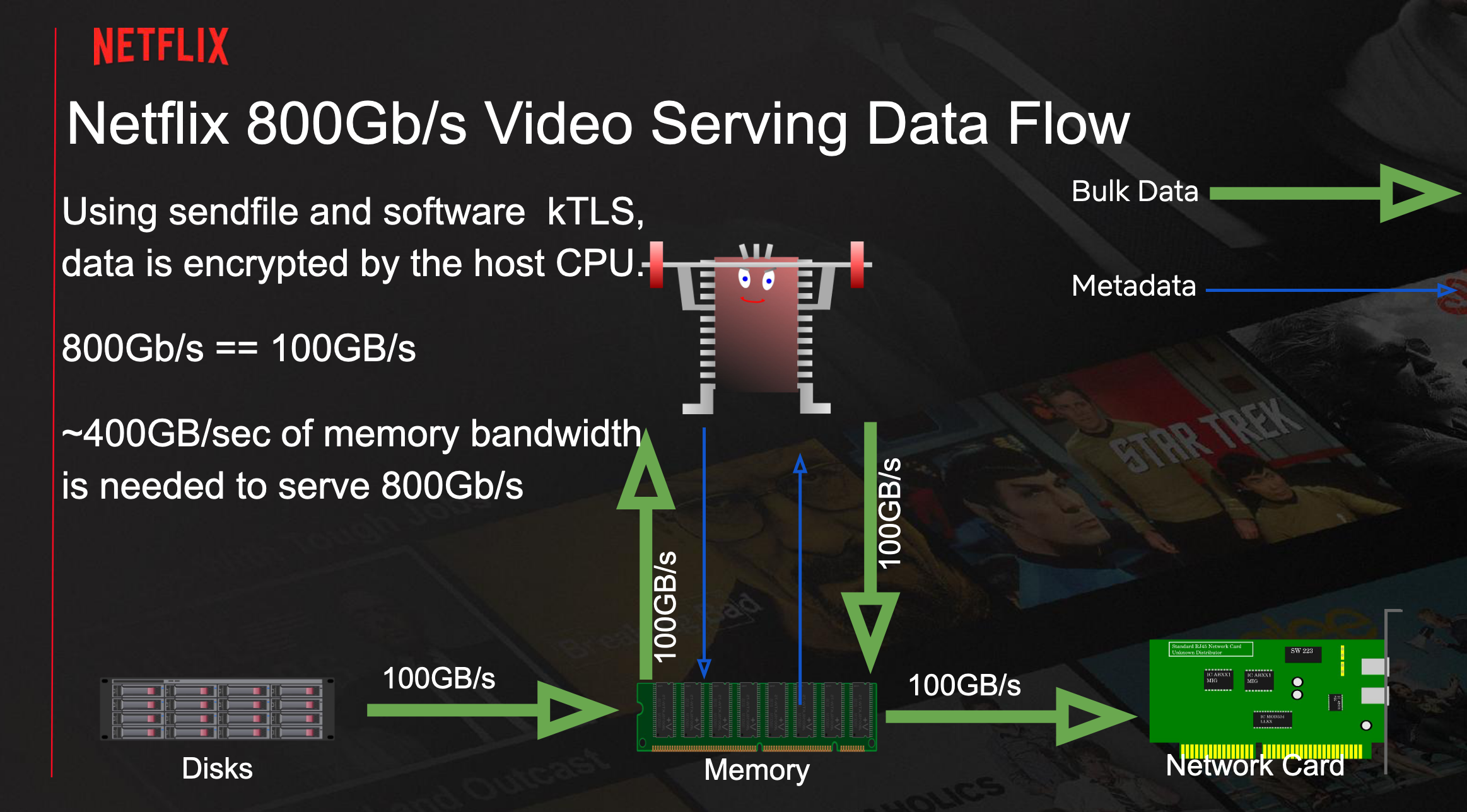

- Sendfile() allows zero-copy transfer of files from disk to network card. This system call however would block the Nginx worker from serving other requests. Workarounds like aio and threadpools didn’t scale well.

- Asynchronous sendfile() implementation allowed Netflix to go from 23Gb/s to 36Gb/s.

- TLS however prevents the usage of sendfile() as data needs to be copied to memory, read, and encrypted then copied back to the kernel, reducing throughput by 66%.

- kTLS (Kernel TLS) restores the original workflow, by handling the initial handshake in userland, and the bulk of encryption in the kernel as part of the sendfile() pipeline.

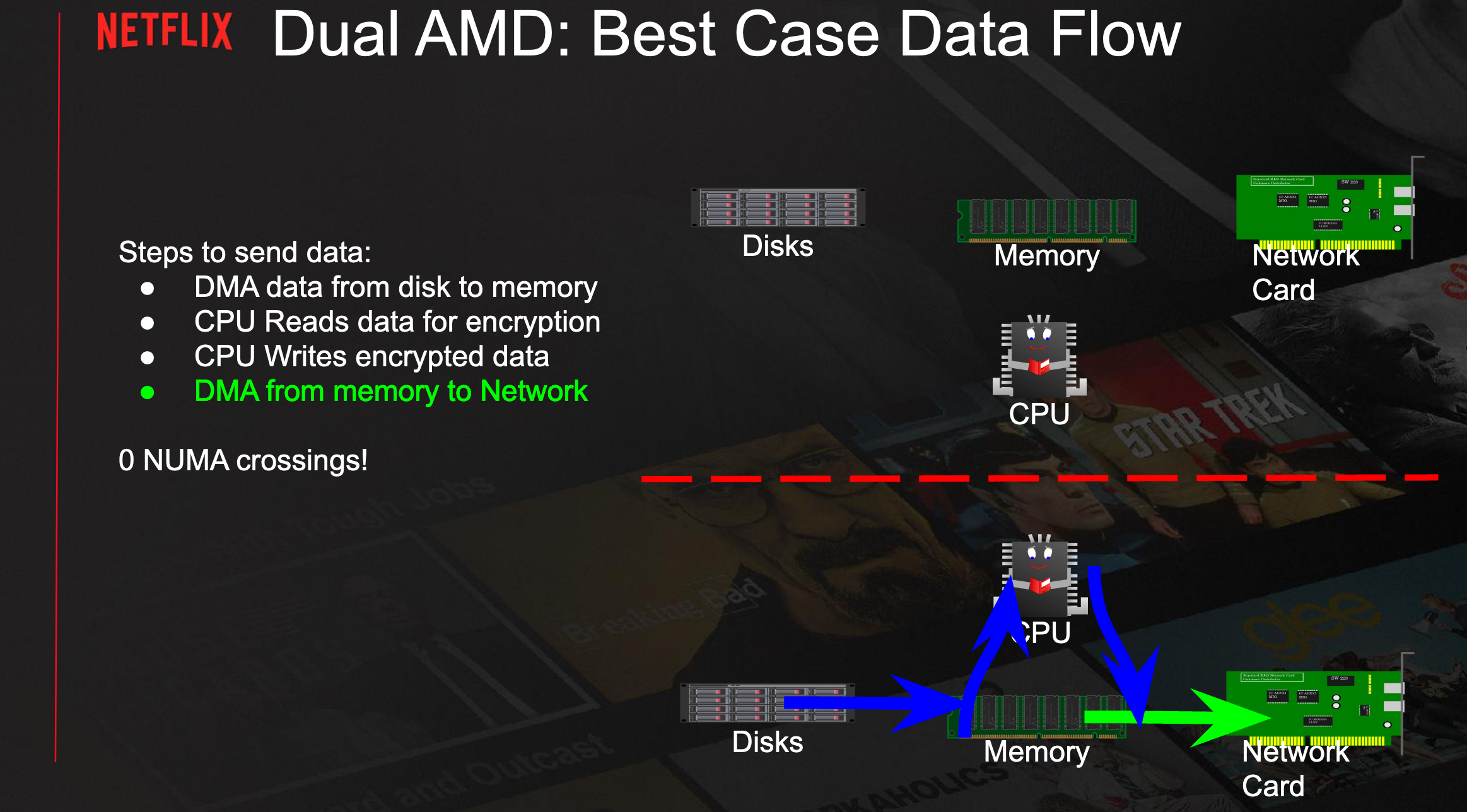

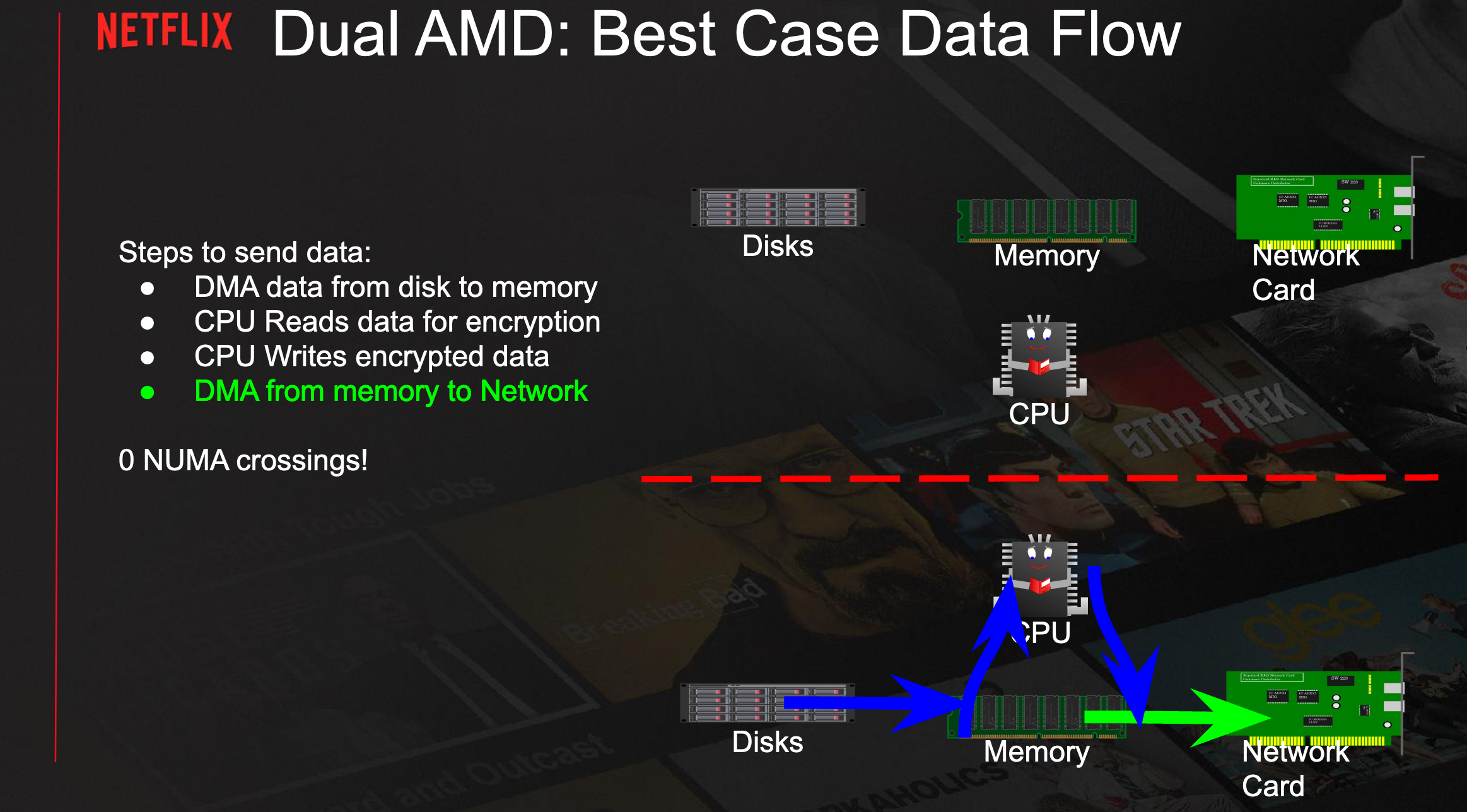

- NUMA (Multi CPU architecture, with resources closer to some cores). Each locality zone (CPU, Memory, Network Card…) is called a NUMA Zone or Domain.

- Crossing the NUMA frontier (eg. disk in zone 1 to network card in zone 2) multiple times leads to fabric saturation and CPU stalls. Best case is when all the pipeline is on the same zone. This is not always possible however.

- Disk siloing (do as much work on the zone where the content is) and network siloing (on the zone where the network connection can from.)

- Inline Hardware (NIC) kTLS: This would allow offloading of almost half of CPU usage, as well as the memory bandwidth between memory and CPU used for encryption.

- NIC kTLS works by establishing the session in user space and passing the crypto keys from the kernel to the NIC.

- Initial tests with network siloing mode were underwhelming at 420Gb/s. Strict disk siloing mode improved the results to 720Gb/s.

- Netflix has no plans for QUIC at the moment, as it would be an efficiency disaster due to the loss of 30 years of optimizations like TSO.

- ChaCha-Poly encryption for kTLS: A/B tests didn’t show any benefits.

- The general advice is that SQLite doesn’t scale beyond a single-user database, and this holds some historic truth to it.

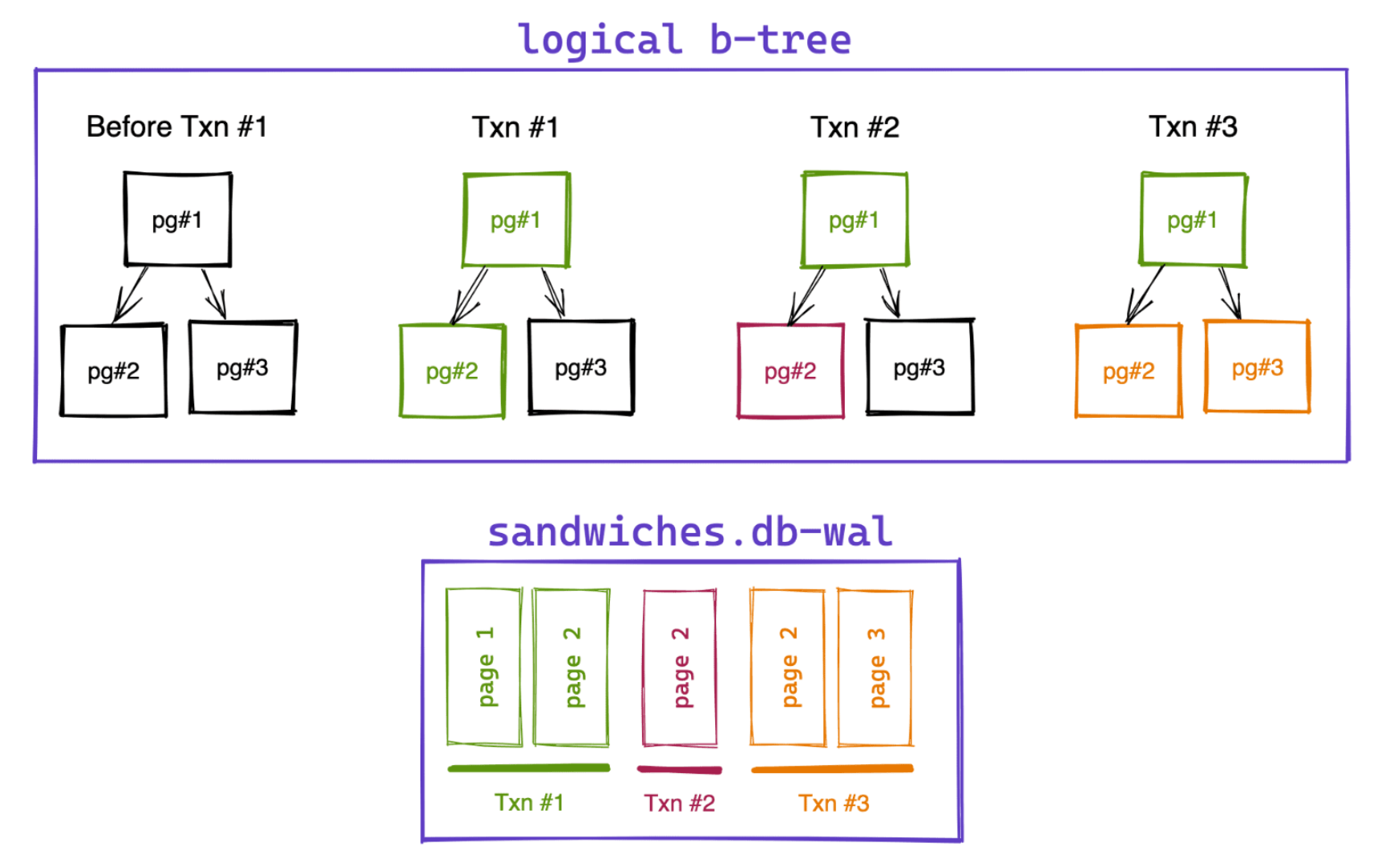

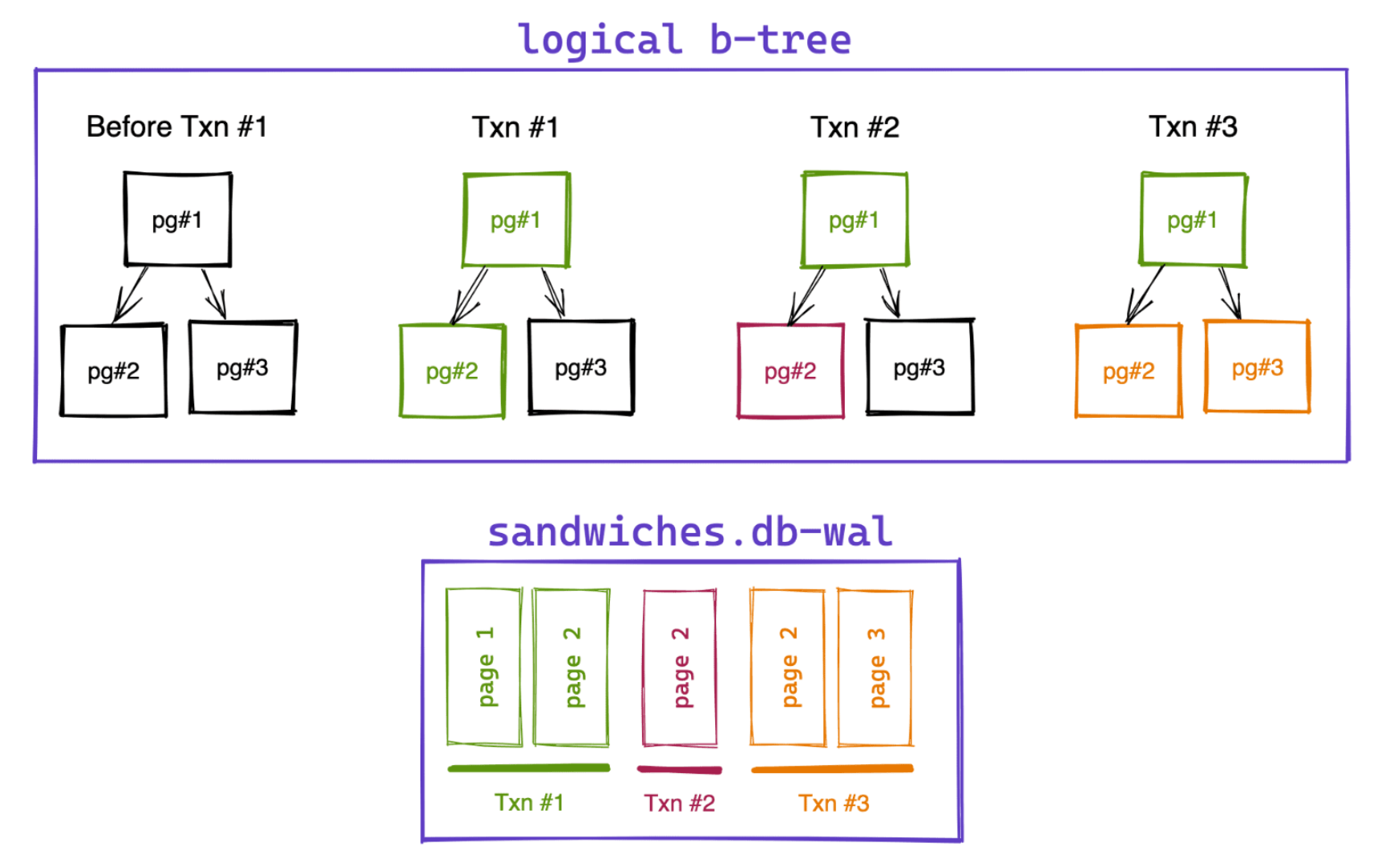

- Switching from rollback journal to WAL journal (writing the new version of a page to another file and leaving the original page in-place) allows SQLite to scale.

- So instead of writing changes to foo.db, they are written to foo.db-wal.

- The WAL file starts with a 32-byte header (magic number, format version, page size, checksum…).

- On data updates, changes (24-byte header + 4KB page) are appended to the WAL file. The header contains information that allows if this is the last committed page in a transaction.

- Combining the .db (logical b-tree) and .db-wal files, snapshots of any point in time can be constructed. This also means that write-transactions don’t block read transactions.

- As the WAL file keeps on getting bigger and bigger, SQLite checkpointing is used to copy the changes back into the main database file.

- A .db-shm (shared memory) file is used to store the database index. This index allows reading the latest version of a page for any transaction.

- Facebook Live started in a hackathon and was fully launched 8 months later.

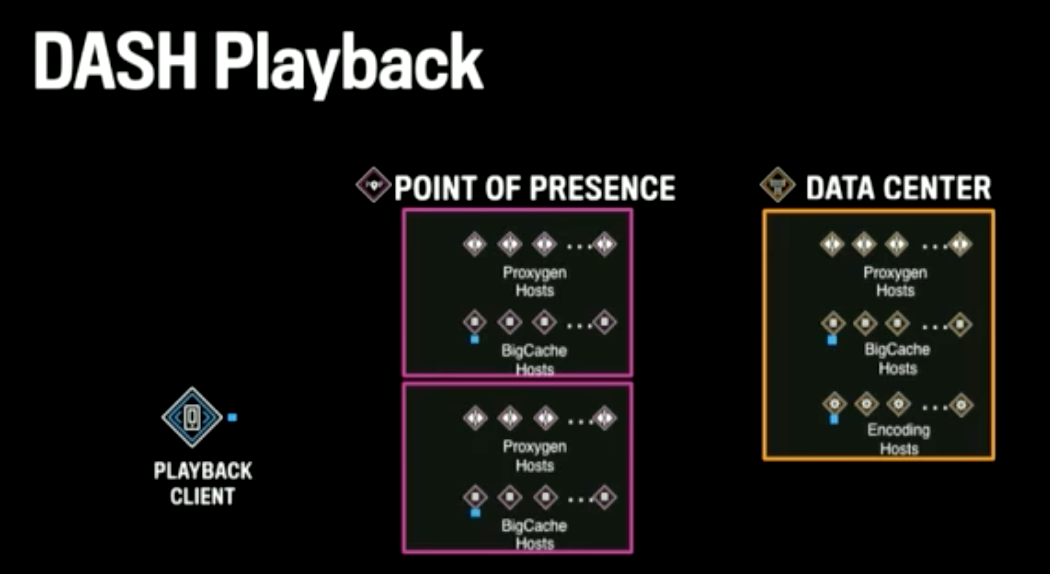

- The broadcasting client connects to FB’s Edge via RTMPS. This connection is forwarded to the Encoding Server in a data center. This is encoded in different formats and distributed to multiple fanout Edge PoPs, which forward it to the playback clients.

- Resources usage

- Compute (Decode/Encode/Analysis)

- Memory (decode/encode)

- Storage (long-term storage for replaying)

- Network (for uploading, but playback is the main user).

- Challenges

- The number of concurrent unique streams: Predictable pattern, which makes planning resources (for encoding, network capacity…) easy.

- The total number of viewers of all streams: Predictable pattern. Effective caching is needed.

- Max number of viewers of a single stream: This is hard to predict and plan for (which stream is going viral and at what point). Unlike premium content, live streams can’t be pre-cached/distributed.

- Requirements for the broadcasting protocol (from streamer to FB): Time to production (deadlines), network compatibility (with Facebook’s infrastructure), end-to-end latency, and application size (part of Facebook apps).

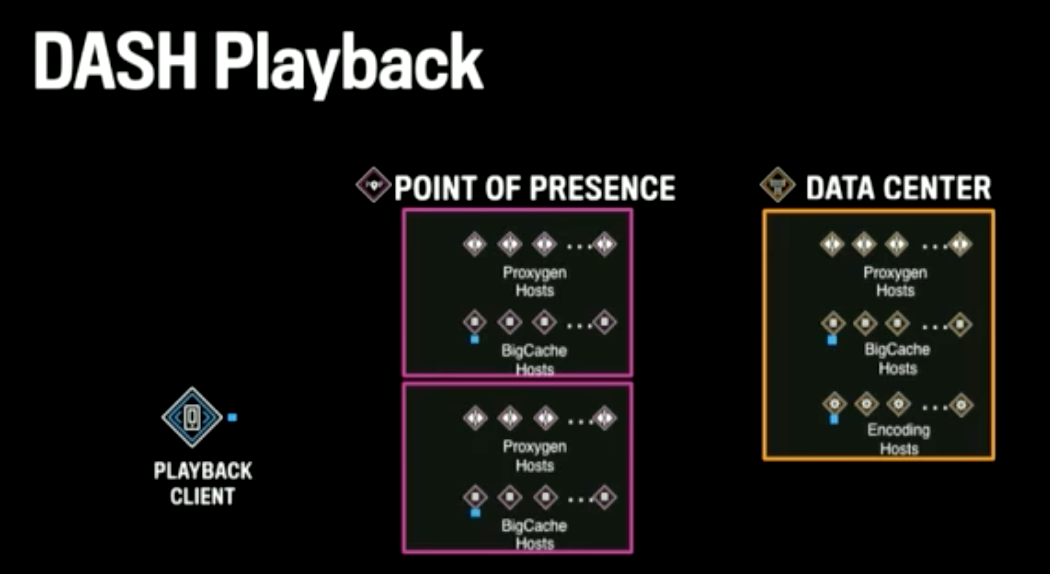

- Facebook data centers are bigger than the PoPs and have more functionality. PoPs are used to connect the broadcasters to Facebook’s network and to cache the streams.

- Hashing of which stream is sent to which proxy host/encoding server in the data center is done based on the stream ID. Initially, it was done based on source IP, which means that when the streamer switches between Wifi/Data, the new connection may end up on a different proxy/server, which leads to jitters for the viewers.

- Playback: Using MPEG-DASH protocol. Contains two files (manifest and media) and works over HTTP.

- There’s a multi-layer (PoPs and Datacenter) caching for DASH playback that reduces latency and network bandwidth.

- Adaptive Bit Rate is done on the broadcaster side used when there are network quality issues. Audio-only broadcast is also a workaround for this.

- Cache-blocking timeout is used in order to have fewer connections from the PoP’s hosts to the data center and prevent thundering herds. If a stream was already requested by a connection, the other connections wait for that connection’s response.

- Among the main lessons: Reliability and scalability are built into the design, you can not add them later.