Depth of Code

Hani’s blog

Hani's Weekly 3: #1

This is the first post of a new series of weekly posts summarizing various articles and resources that I’m reading and learning from. The content is going to be focused on Software Engineering mostly, but not exclusively.

I had many inspirations for this: Turning Pro and The War of Art (Steven Pressfield), 5-Bullet Friday (Tim Ferriss) and more recently Building a Second Brain (Tiago Forte).

I’m committing to 10 weekly posts for the being time, to see where this goes.

How Discord Supercharges Network Disks for Extreme Low-Latency

- Discord runs a set of ScyllaDB NoSQL database clusters to store their enormous data, serving 2 million req/sec.

- When query rate is low, database latency is not noticeable due to parallel handling of queries and not blocking on a single disk operation. At some point, the database starts blocking on disk seeks before issuing the next one, which eventually leads to worse performance. This could be measured with the disk operations queue size.

- GCP’s Persistent Disks: Currently used by Discord, they can be dynamically attached/detached and resized on the fly without downtime. They aren’t connected directly to the server however and are somewhere in the local network, which makes latency very bad.

- Local SSDs: Not a viable option due to missing features such as point-in-time snapshots, and the risk of losing data if something happens to the host they are connected to.

- Some of the features from both options aren’t needed: Write-latency isn’t as important (read-heavy workloads), and zero-downtime resizing can be substituted with better storage growth planning.

- By combining Local SSDs with Persistent Disks, all requirements (point-in-time snapshots, low read-latency, database uptime guarantees) could be met.

- A “Super-Disk” could thus be created by using Local SSDs as a write-through cache for the Persistent Disks.

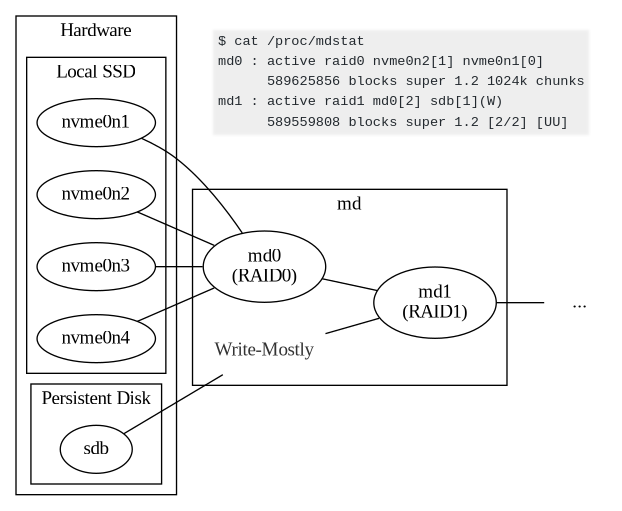

- The “md” driver on Linux allows creating a “Software RAID”, combining multiple disks.

- RAID0 is used to combine multiple Local SSDs into a large low-latency virtual disk, which is then RAID1 combined with a Persistent Disk that was marked as “write-mostly”. The Persistent Disk will be read only if there are no other options.

- This new configuration decreased disk operations queues and overall wait time.

How to Design a Scalable Rate Limiting Algorithm

- Rate limiting is needed in many scenarios: cost control, maintaining the quality of service (against excessive usage and DoS attacks), limiting how much sensitive data is exposed by API (via scraping, or brute forcing), etc,.

- There are various algorithms:

- Leaky bucket: Think of it as a queue with a size limit, dropping any excess requests. This smooths out any bursts of traffic while being memory-efficient and easy to implement on a load-balancer. The system might be starved with old requests though.

- Fixed window: Using a counter that gets restarted every X time (eg 60 seconds). This ensures recent requests are still processed, but doesn’t handle bursts near the window boundaries. You may also have a thundering herd issue if many consumers are waiting for those fixed window resets.

- Sliding Log: Keeping track of processed requests in a time-stamped log, and discarding older entries. This algorithm is very precise but doesn’t scale well as it is resource-intensive (memory footprint, computing per-consumer usage across multiple servers…)

- Sliding Window: A hybrid approach, tracking the current window and the previous one, we calculate the ratio eg, 15 seconds into the new window means the current usage is 25% of the current count + 75% of the previous window’s count. This is not as precise as the sliding log algorithm, but is more scalable, and avoids problems in other algorithms like starvation of new requests and bursts at window boundaries.

- In a distributed system, there needs to be a synchronization policy between nodes. Otherwise, a consumer would be able to bypass their quota by hitting different nodes. There are multiple solutions for this:

- Sticky session: A consumer’s requests get sent to the same node.

- Centralized data-store (Redis or Cassandra) to keep track of the counts, but this comes with increased latency and race conditions (with a “get-then-set”) issues.

- Using locks to prevent race conditions can be a significant performance hit. It’s better to rely on atomic operations that allow incrementing and checking values quickly.

- For latency, it’s possible to store the counts locally for each node, and periodically send them to the centralized store. This is a more relaxed, eventually consistent model. There’s a tradeoff between shorter sync times (less divergence of data points) and longer ones (less read/write pressure on the datastore, and decreased latency).

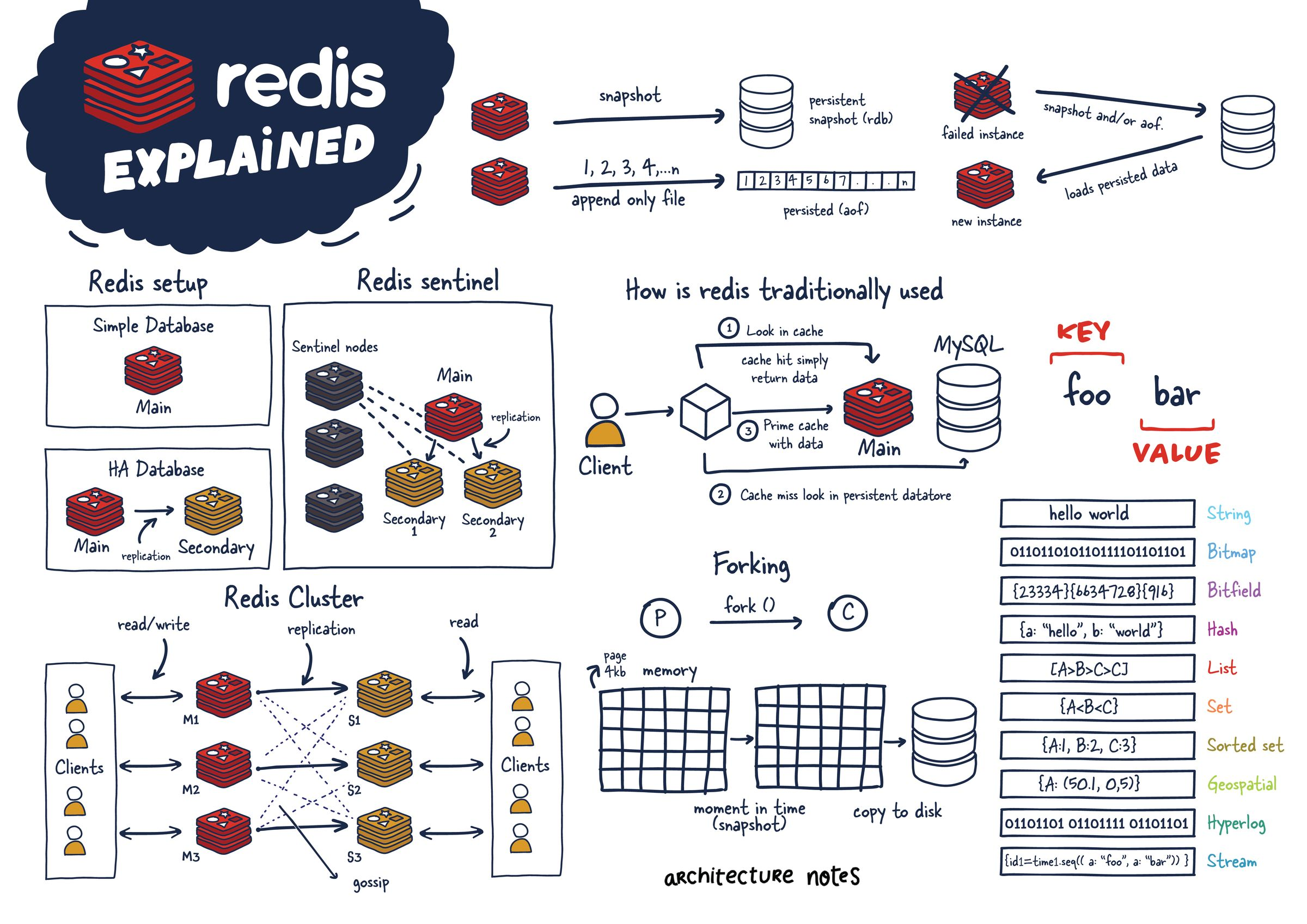

Redis Explained

- Redis is an in-memory datastore that is usually used to cache data and thus improve performance. But for some use cases, it can even be used as a primary database that provides enough guarantees.

- There are four different ways to deploy Redis, depending on the needs: Single Instance, Redis HA, Redis Sentinel, and Redis Cluster.

- Single instance: Mainly for caching, as it lacks fault tolerance and high availability. Persistence is achieved by a forked process (on some intervals) that provides point-in-time snapshots.

- Redis HA: Secondary instances are kept in sync with the main one, by receiving data writing commands from it. This helps with scaling reads by eliminating the single point of failure and providing failovers in case the main instance is down.

- Replication: Every main instance has a Replication ID and an Offset that is incremented on every action. If the secondary is a few offsets behind, it will receive the remaining commands. If there’s disagreement on the Replication ID or the Offset (eg. when a secondary is promoted to main, it creates a new Replication ID), a full-synchronization happens via RDB snapshot. The previous Replication ID could be used as a common ancestor in order to perform a partial sync only.

- Redis Sentinel: Sentinel processes provide monitoring (are main and secondary instances functional ?), failure notification, service discovery like ZooKeeper (Which instance is the main instance ?), and failover management (If the main instance isn’t available, and a quorum of sentinels agrees on it).

- The quorum value is context-dependent, but usually, it’s recommended to run three nodes with a quorum minimum of two.

- A few things could go wrong with this setup, like a network split that would put the main instance with a minority group of nodes. The writes would be lost after the network recovery.

- As replication is asynchronous, there are no durability guarantees still. This has tradeoffs. To mitigate this, the main instance needs to replicate to at least one secondary and track the acknowledgments

- Redis Cluster: This allows horizontal scaling, via sharding when data can’t fit on a single node any more. The key is mapped to one of the 16k hashslots via a hash function. If there are 2 nodes, they would share the 16k slots space (0-8K for M1, 8K-16K for M2). When a node is added, only parts of the slots (5k-8k to M2, and 11k-16k to M3) are copied.

- Gossiping between main instances and secondary ones determines the health of the cluster.

- Persistence: In Redis, usually speed comes first, ahead of consistency guarantees.

- RDB Files: A point-in-time snapshot at configurable intervals. Data between snapshots is lost. It relies on forking the main process which could be problematic for large datasets but is fast to load up.

- AOF (Append-Only File): The original dataset is constructed from all the write commands that were written to the file. The write commands are buffered in memory, and eventually flushed to disk with fsync(), which leads to some I/O to be done. by the main process. This format is less compact on disk but can be compacted in the background.

- Forking: Copy-on-write is leveraged (child process shares physical memory with parent process until modified) to make the persistence more performant.